Béla Bartók

(25 March 1881 – 26 September 1945)

Béla Bartók’s life and work seem particularly relevant during a period of European integration that is just happening before our eyes and to an extent that was previously certainly never even dreamt of, especially not during the composer’s life when Europe was repeatedly divided by two “World Wars.” Bartók’s unquenchable interest in (and, as he himself expressed, love for) the peasant music of different nations, ethnicities, groups and territories has set an unparalleled example for us today.

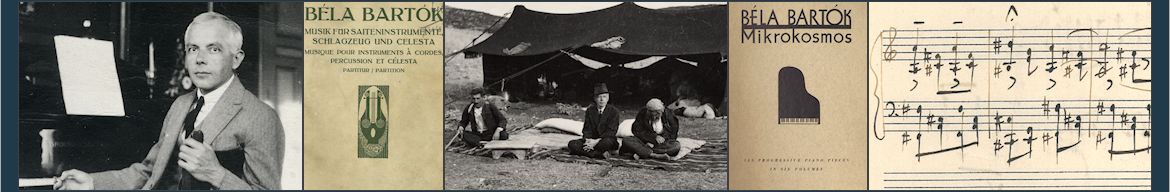

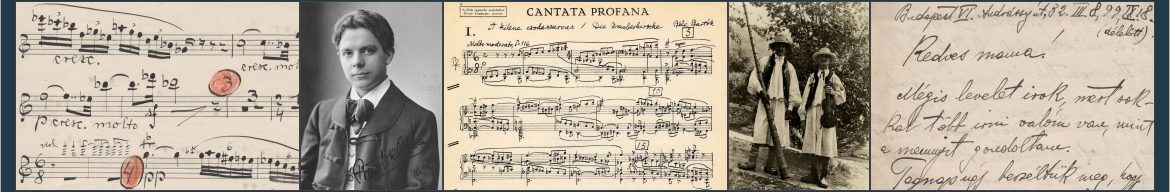

Béla Bartók, composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist, was born in Nagyszentmiklós in Hungary (now Sînnicolau Mare in Romania) in 1881 and died in New York in 1945. His childhood was plagued with various illnesses. After the early death of the father (Béla Bartók, Sr.), when he was only seven years old, his mother, Paula Voit, struggled to raise her two children, Béla and her then three-year-old daughter, Elza, wandering from town to town before finally settling in Pozsony (Pressburg, now Bratislava, Slovakia) where Béla received thorough musical instruction and completed his grammar school studies. Following in Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi’s footsteps, four years his senior and also coming from Pozsony, he studied piano (with Liszt pupil István Thomán) and composition (with Hans Koessler) at the Budapest Royal Academy of Music between 1899 and 1903. Although he was immediately recognized as a powerful talent as both pianist and composer, his career was not an easy one. After writing his first grand-scale “nationalist” compositions (notably the Kossuth Symphony, a work soon withdrawn, the Rhapsody for piano and for piano and orchestra, and the First Orchestral Suite), he discovered peasant music as a more indigenous and more “authentic” source of something particularly “Hungarian” in music and began to collect folk music on a regular basis and to write modern, often experimental works (Fourteen Bagatelles for piano, First String Quartet) using folk music-derived modernistic material. The development of his new musical style was also influenced by the personal crisis of his unrequited love towards the violinist Stefi Geyer in 1907–1908 whose crucial artistic document is the posthumously published (“1st”) Violin Concerto. In 1909 he married Márta Ziegler who bore him his first son Béla Bartók, Jr. (1910–1994). Besides being piano professor at the Academy of Music in Budapest from 1907 on, Bartók gradually developed into a full-scale scholar. For more than a decade, he devoted most of his energies to field trips to remote areas of pre-First-World-War Hungary that also included large areas of partly or mainly Slovak and Romanian speaking ethnic groups. Quite early in his research, Bartók turned to the collection of folk music from the minorities as well thereby significantly contributing to the then new field of comparative ethnomusicology. He was particularly interested in archaic features of peasant music that he described as a “natural phenomenon” whose study should be considered as “scientific” work. His extensive collections in Hungary include some 3500 Romanian, 3000 Slovak and 2700 Hungarian, as well as some Serbian and Bulgarian melodies.

Béla Bartók, composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist, was born in Nagyszentmiklós in Hungary (now Sînnicolau Mare in Romania) in 1881 and died in New York in 1945. His childhood was plagued with various illnesses. After the early death of the father (Béla Bartók, Sr.), when he was only seven years old, his mother, Paula Voit, struggled to raise her two children, Béla and her then three-year-old daughter, Elza, wandering from town to town before finally settling in Pozsony (Pressburg, now Bratislava, Slovakia) where Béla received thorough musical instruction and completed his grammar school studies. Following in Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi’s footsteps, four years his senior and also coming from Pozsony, he studied piano (with Liszt pupil István Thomán) and composition (with Hans Koessler) at the Budapest Royal Academy of Music between 1899 and 1903. Although he was immediately recognized as a powerful talent as both pianist and composer, his career was not an easy one. After writing his first grand-scale “nationalist” compositions (notably the Kossuth Symphony, a work soon withdrawn, the Rhapsody for piano and for piano and orchestra, and the First Orchestral Suite), he discovered peasant music as a more indigenous and more “authentic” source of something particularly “Hungarian” in music and began to collect folk music on a regular basis and to write modern, often experimental works (Fourteen Bagatelles for piano, First String Quartet) using folk music-derived modernistic material. The development of his new musical style was also influenced by the personal crisis of his unrequited love towards the violinist Stefi Geyer in 1907–1908 whose crucial artistic document is the posthumously published (“1st”) Violin Concerto. In 1909 he married Márta Ziegler who bore him his first son Béla Bartók, Jr. (1910–1994). Besides being piano professor at the Academy of Music in Budapest from 1907 on, Bartók gradually developed into a full-scale scholar. For more than a decade, he devoted most of his energies to field trips to remote areas of pre-First-World-War Hungary that also included large areas of partly or mainly Slovak and Romanian speaking ethnic groups. Quite early in his research, Bartók turned to the collection of folk music from the minorities as well thereby significantly contributing to the then new field of comparative ethnomusicology. He was particularly interested in archaic features of peasant music that he described as a “natural phenomenon” whose study should be considered as “scientific” work. His extensive collections in Hungary include some 3500 Romanian, 3000 Slovak and 2700 Hungarian, as well as some Serbian and Bulgarian melodies.

From 1906, he often worked together with fellow composer and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967). In search of ancient musical cultures, Bartók even collected rural Arab songs in Algeria in 1913 and later he visited Turkey in 1936. His collecting activity, however, practically ended in 1918 soon before the partitioning of Hungary in the wake of the First World War and the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when fieldwork on territories with some of the richest folklore traditions became impossible. Instead, he carried on his ever more detailed scholarly transcriptions and systematization of his Slovak and Romanian collections. In the meantime he also published the first scholarly monograph on Hungarian peasant songs (A magyar népdal, 1924, Das ungarische Volkslied, 1925, Hungarian Folk Music, 1931) that also included a large selection of examples. Between 1934 and 1940, he worked on the preparation of an edition of the 13,000 Hungarian songs collected by then and preserved at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. In 1937/38, he was also involved with a series of recordings for the Pátria series. For his ethnomusicological work he became elected member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1935.

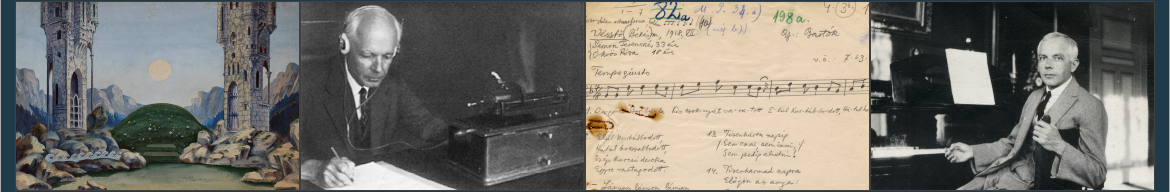

By the end of the First World War, especially after the successful premières of his two stage works (to librettos by Béla Balázs), the ballet, The Wooden Prince (1914–17), and the opera, Duke Bluebeard’s Castle (1911) in 1917 and 1918, respectively, he had established himself as the leading composer of his generation in Hungary. From 1918 on, his compositions were published by Universal Edition, Vienna, and he could start to build up an international career as pianist and, more importantly, composer regularly visiting Paris, London and other musical centres of Europe. He also toured the United States and the Soviet Union in the later 1920s.

1923 marks his divorce from his first wife and his marriage with his young pianist pupil, Ditta Pásztory. Their child, Péter Bartók, was born in the following year.

Bartók’s piano music, e.g. Allegro barbaro (1911) and Outdoors (1926) and his pedagogical compositions, e.g. For Children (1908–1911) and Mikrokosmos (1932–39), as well as the Forty-Four Violin Duos (1931) occupy a significant place in 20th-century composition, and his six String Quartets (composed between 1908 and 1939) are considered among the finest modern representatives of the genre. Some of his larger scale orchestral works also had a significant world-wide success from their first performances, especially the Dance Suite (1923) and Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936), the first of his compositions commissioned by the Swiss conductor and patron Paul Sacher. His pantomime, The Miraculous Mandarin (1918–19, orchestration 1924 on a scenario by Menyhért (Melchior) Lengyel), is probably his most daringly and most radical modernist masterpiece whose subject matter caused outrage at its première in Cologne in 1926. These works put him close to the rank of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, the two most famous composer innovators of his generation. As lecturer, author of numerous studies and articles, and editor of extensive volumes of folksong collections, Bartók was considered as a leading authority on East-European folklore.

Following Nazi Germany’s occupation of Austria, he changed publishers to the London based Boosey and Hawkes and started to arrange for his departure from threatened Hungary and Europe and, in 1940, he went to the United States. Apart from giving concerts, he was mainly occupied at Universities, Columbia University, from which he received an honorary doctorate and where he worked at the transcription and systematization of Milam Parry’s South Slavic collection, and Harvard University. During his American exile, his fatal illness, leukaemia, soon made its appearance. Still, he was able to compose some great masterpieces, such as the Concerto for Orchestra (for conductor Serge Koussevitzky, 1943), the Sonata for Solo Violin (for the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, 1944) and his Third Piano Concerto written for his wife, and he was able to complete the preparation for publication of most of his folk music collections, which were, however, published only posthumously.

While during and immediately after the war he was deeply concerned with his homeland’s fate and future, and he never gave up his Hungarian citizenship, he did not consider it timely to return to Hungary. Decades after his death, his remains were solemnly transferred from New York to Budapest by his two sons and reburied at the Farkasrét Cemetery where it now rests.